How can you prove the alcohol content of your whisky, brandy or gin? This question has long been of interest to distillers, excise collectors, publicans and serious drinkers. This intriguing and inventive box of calibrated glass bubbles provides one answer. It is also a singular example of the significance of glass as a material of science, utility and beauty.

Another name for this hydrometer set is ‘gravity beads’, because each one sinks in liquids of certain specific gravities and floats in others. They have also been called ‘aerometrical beads’ and ‘hydrostatic beads’. But beads sound boring, and the scientific adjectives are weighty. I prefer ‘philosophical bubbles’ because these lightweight spheres are well worth thinking about. They were designed with understanding, crafted with skill and tested with authority. This museum object is no intellectual lightweight, no mere curio in the history of science.

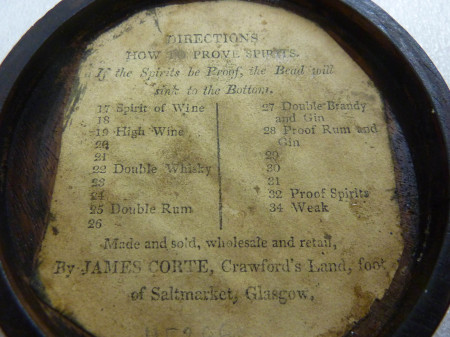

Alexander Wilson invented this type of hydrometer in Glasgow in the 1750s. Little is known about the maker of this set, James Corte, except that he traded from premises in Glasgow’s Saltmarket. That’s the area where James Watt worked as a scientific instrument maker before gaining fame as an engineer, so perhaps the two men were acquainted. Perhaps they discussed philosophy over a dram of Scotch whisky, making for just two degrees of separation between the Museum’s philosophical bubbles and its famous Boulton & Watt engine.

Either Corte was a glassblower himself, or he employed a glassblower to make hundreds of bubbles, each with a short stem where it was detached from the blowpipe. He would have tested each bubble’s specific gravity and etched the number on it that matches the list stuck inside the lid of the box. The number is opposite the stem so that it can be seen from above when the bubble floats, its stem pointing down because the centre of gravity is closer to that part of the bubble.

Imagine being among the first people to make glass, to get a glimpse of its properties and potential. It is a truly amazing material, transparent and long-lasting, made since antiquity simply by heating sand with sodium and calcium carbonates, but now available in a range of formulations.

Glass is essential to art, science, architecture and our screen-based culture. It contains food and drink and chemical experiments while making them visible, and it cocoons drivers, pilots and passengers while allowing them to see outside their vehicles. As optical fibre, it carries huge volumes of information around the world. And it opens up realms of knowledge as a vital component of microscopes, telescopes, spectroscopes and a host of other scientific instruments that help us understand the natural world, the things we make (including alcoholic drinks) and ourselves.

Written by Debbie Rudder, Curator