I’m currently finishing up a 3-month internship in the Curatorial department of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (MAAS). I embarked on this three-month internship without any background in museum work or studies. My internship application seemed like a shot in the dark because it could be aptly summarised in one sentence, ‘Hi, my name is Erica, long-time fan, first time applicant.’

I’m a Science (Pharmacology) / Law student at the University of New South Wales. I have always been interested in science and the way in which technology and scientific concepts, both new and old, have been communicated to a wide range of audiences. As a child, I always enjoyed learning new things and never failed to ask all the annoying (but essential) questions starting with “Who”, “What”, “How” and “Why”. I was never able to shake this habit and it has followed me through to adulthood. Fortunately, in places like museums, my perennial fascination, curiosity and questioning are widely accepted, even encouraged.

A Curatorial Internship at MAAS has been a fantastic opportunity to expand my knowledge and interests in science, and has helped me to develop the skills to communicate and share my understanding with others. I have assisted in research and documentation for existing objects in the MAAS collection and prepared cases to acquire new objects such as scientific instruments and archaeological materials. I have also had a more hands-on experience working with the objects I was researching, as well as being taken on tours of the Museum’s different sites and collection stores. Overall, I have learned so many things over a relatively short period of time.

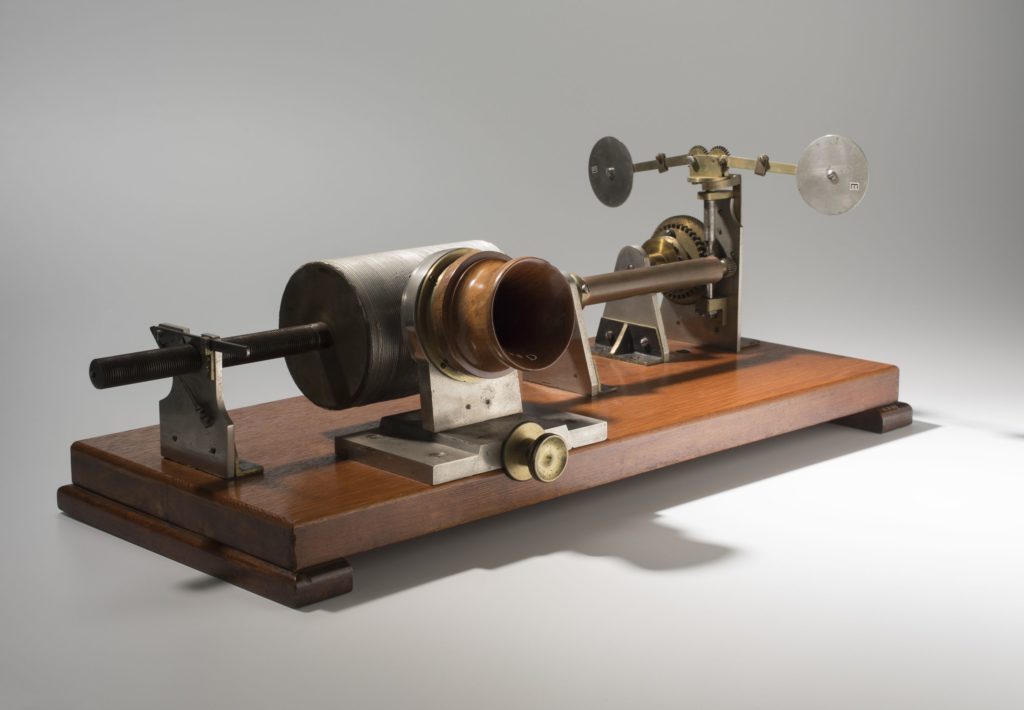

For the first few weeks of my internship I worked on researching, documenting and updating object records from the Museum’s collection of timekeeping and recording devices. One of the objects I became most familiar with, and fond of, was the Edison Tinfoil Phonograph. It was one of the earliest recording and playback machines invented by Thomas Edison in 1877 and manufactured and sold by the London Stereoscopic Company c1885-1891.

The machine captured sound vibrations of a person’s voice through a mouthpiece which caused a needle to vibrate and create indentations on a tinfoil-wrapped cylinder. When rewound to the beginning, the phonograph could then reproduc the original sounds. The phonograph was only one of 1,093 inventions patented by Thomas Edison. Unfortunately, it wasn’t his most successful invention, primarily due to its poor sound quality and fragile tinfoil structure. However, it was the invention that spearheaded the earliest recording innovations that eventually launched the global recorded music industry which today is worth over USD$150 billion, and totalled just over USD$17.3 billion in revenues in the last year. Although it was not one of the most successful innovations of his time, I grew to appreciate it as an invention which allowed for the development of lasting technological and cultural contributions the world over.

In addition to my research I also received object handling training and had the chance to touch and see the objects I was writing about. Things such as flashlights, books, tea cups and tea gowns all required specific methods of handling and care. Once an ordinary item is acquired by the Museum, it is no longer handled like any other household item. A kettle, for example, has to be checked for any detachable or unhinged parts before lifting, and since the handle presents a possible point of weakness, it should never be used to pick up the object. Getting from A to B with an object was no longer a matter of just lifting and moving; it required gloved hands, risk analysis and careful following of procedures to ensure the object remained in same state from lift off to landing. For most curators, this process probably becomes second nature but in my head, each item still screams ‘Do not touch’.

Over the course of my internship I have learned to view everything in the museum with a different lens. A label can share some interesting facts about an object but each item in the collection has a richer story to tell. Behind the scenes, I have not only had the chance to ask and learn about the whos, whats, hows and whys of different objects, but have also gained the practical experience to uncover these answers for myself.

Written by Erica Balilo, Curatorial Intern, 2018

Under the supervision of Sarah Reeves, Assistant Curator

More information about MAAS Tertiary Internships is available on our website here.

References:

International Federation of the Phonographic Industry, Annual Global Music Report, 2018