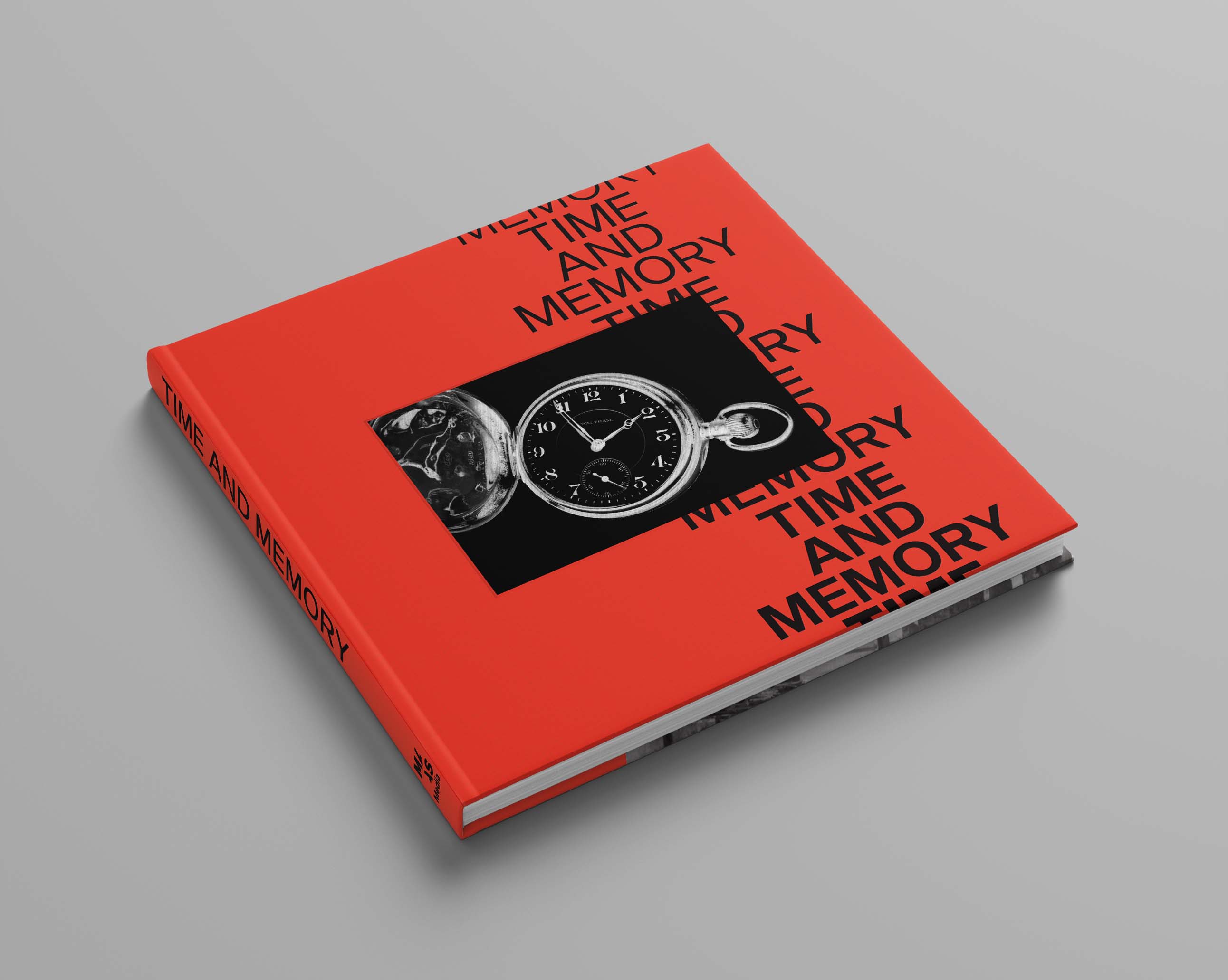

The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences has just launched a new publication, Time and Memory, the second in the MAAS collection series which is supported by the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund. In his introductory essay ‘The Shape of Time’, Principal Curator Matthew Connell places the Museum’s collection within the context of humanity’s understanding and experience of time, and our relationship with memory. Here is an edited extract.

The more than 500,000 objects held in the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences collection can all give us access to past events. For some, there is almost no information available, but often by their substance and form alone, we can understand older processes and see how ideas have changed or persisted over time. Each ultimately speaks of the period in which it was made and used.

In the past 30 years, as MAAS strives to represent the technological changes that define our age, we have acquired into the collection a number of memory technologies. The form of digital ‘memory’ has changed several times over the past 70 years. We also collect examples of media technologies, systems for storing and communicating information and ideas — extensions of our memories. Digital memory, while initially collected as a component of a digital computer, has taken over the role of the traditional information and storage media; however, its fragility has caused concern in the museum and archive sectors.

Within the Museum’s exhibition spaces and on the shelves in its storage facilities are a number of clocks and other time measurement and recording devices. The development of time-keeping and the invention of the clock have had an enormous influence on western culture. Today it is the technology we have for telling and structuring our time that seems to dominate our understanding of the world and how we live within it. Financial years, school years and parliamentary terms impose deadlines on our work and family lives. We spend little time regarding our world and lives from broader temporal perspectives.

Museums have often been referred to as time machines; they are certainly deeply concerned with time. Current debates within contemporary museology include questions about which periods of time they might best represent. Should they focus on the past or be more attentive to contemporary issues, or is their role to speculate about the future?

Time is so integral to everything we comprehend and to the way in which we conduct our lives that it is easy to take it for granted, to assume that our relationships to and understanding of time are part of the natural world, unchanging, proceeding and experienced by all people in the same way across space and history. But that understanding itself, especially within western culture, changes over time. The concept of time is certainly tied to the natural world but its measurement is a very human contrivance, and the technologies we have developed to undertake and refine that measurement have changed not only the way we understand time but also the way we think in general.

Visitors to the Museum will be familiar with the Strasburg Clock model. Built from a postcard image in 1887–89 by eccentric Sydney clockmaker Richard Bartholomew Smith, it drew big crowds until at least the 1970s, and it still has visitors sitting quietly in anticipation of the procession of apostles — complete with a rooster crowing at Peter’s denial of Jesus, and the Devil hiding in the corner as Judas makes his appearance. This spectacle reminds us of the Christian European origins of the colonising culture of New South Wales, and also takes us to the beginning of mechanical time-keeping.

Mechanical clocks appeared in Europe in the 1300s. The Strasburg Cathedral clock in France, which inspired the MAAS model, was built in 1354, predated by only a handful of known examples. The cathedral clock, through its mechanisms, represents many aspects of the heavenly patterns we see, the phases of the Moon and positions of the planets. It was built for spectacle, bringing glory to God and to its makers, and divided up the day so that prayers could be attended regularly and frequently.

The rotation of the Earth on its axis gives us day and night. Clocks introduced the division of day and night into 24 equal periods, or hours. The hours provided a timetable for prayer, and people started to organise themselves around bells that called out the hours. This was the beginning of a completely new conception of time that has continued to this day.

The first clocks were not very accurate. For the next 200 years the mechanisms of the cathedral clocks and their relatives would lose at least 15 minutes a day. The incorporation of the pendulum in the 1600s improved things considerably. A good pendulum clock might only be out by one to ten seconds a day. But sundials were still used to calibrate them. By the 18th century new scientific methods and knowledge were being brought to bear on clockwork, helping to improve accuracy. This process of improvement continues, driven by and serving science.

Sydney Observatory was built in 1858 with the primary purpose of determining accurate time for New South Wales. It was built on a meridian (line of longitude) and the transit telescope at its centre was used to determine exactly when certain stars crossed directly overhead. Observing the Sun and stars from a known position provides the exact time. That time was then communicated to those who required it, particularly the ships in the harbour, by means of the time ball that is still on the Observatory tower and dropped each day at 1.00 pm.

The MAAS collection series is supported by a grant from the Copyright Agency Cultural Fund.

Time and Memory is available from the MAAS Store, selected bookstores nationally or online.

Time and Memory features essays from talented Australian writers Samuel Wagan Watson and Vanessa Berry, as well as contributions from MAAS authors. We’ll be publishing further extracts from the book on Inside the Collection in coming months.