Guest post by Artist in Residence, Lily Hibberd

Lily Hibberd is an interdisciplinary artist and writer working with frontiers of time and memory. Her projects are developed in long term place and community-based collaboration, and research with local artists, scientists and historians through combinations of performance, writing, painting, photography, sound, moving image and installation art.

This blog has been created for ‘Boundless – out of time’, Lily’s month-long artist and research residency at Sydney Observatory. View all of Lily’s posts here and read the introduction to Boundless Remapping Sydney Meridian. Presented by Powerhouse Museum as part of NIRIN, the 22nd Biennale of Sydney 2020.

Follow Kent Street a few metres to reach the T intersection with Druitt Street. Cross over to the corner of Town Hall House (both loved and hated as an exceptional example of Brutalist architecture). About five metres along is a hidden stairwell, follow this through to the rear of Sydney Town Hall and follow the signs inside to Marconi Terrace.

Here we are now at the end of our venture to retrace Sydney Meridian, back on the exact line of the first official measure of 151° 12′ 23.1″ E. – as close as I could get on Google Earth… The terrace was renovated fairly recently, so if you’re lucky you’ll happen on a party and a well-earned beverage after such a long walk!

By coincidence (or not?), the terrace has an historical connection to the advancement of imperial timekeeping in Australia. It is named after an Italian named Guglielmo Marconi – who was instrumental in the first wireless transmissions made before the end of the 1880s, and who was not shy to monopolise the global corporate expansion of radio technology.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the British Empire needed to maintain its universal dominance, for which it had to be ahead of the communications game, especially to keep in touch with its conquered colonial subjects. Not only were Britain’s colonies numerous, they could not have been farther away than Australia.

While radio was one of the most radical inventions to support the expansion the global empires, in the early 20th century it was primarily used for time signal transmission for ocean navigation. In 1908, the Bureau des Longitudes established a daily time signal from the Eiffel Tower to assist with longitude determinations, a service that is still transmitted twice daily to this day. Broadcast time signals were rapidly implemented worldwide, after 1912 the Bureau des Longitudes International Time Conference inaugurated a globally consistent method for time signal transmission.

But in terms of setting up a transnational radio network, the British lagged behind in comparison to the French and Germans, mainly due to the threat radio posed to its monopoly on the network of submarine telegraph cables. But then the First World War made it impossible to wait any longer, and so the British determined to build their own ‘Imperial Wireless Chain’. On top of this, the Australian Prime Minister of the time, Andrew Fisher, who was generally very supportive of British interests, – decided to make his own deal with Marconi and establish a company independent of ‘Mother England’ – prompting a major political rift between the two governments.

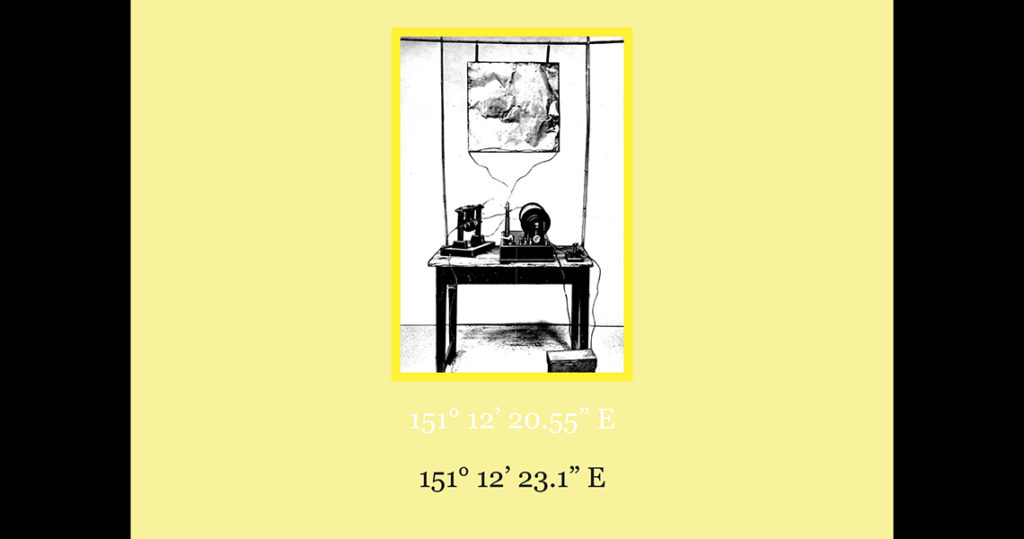

Marconi, for all his flaws, was remembered favourably in Australia. The Powerhouse Museum has even conserved a number of the key components from this setup, including an induction coil, a high power triode broadcast transmitting valve, and a wireless telegraph wire detector. Experts are welcome to inform us about how this actually worked!

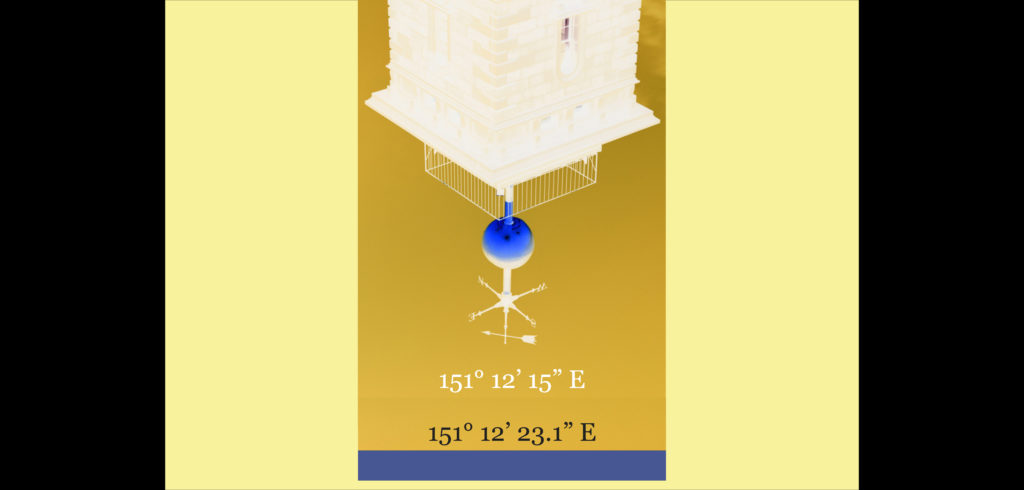

In any case, for his role in helping to make one of the rare historical moves for independence from British influence at the time, Marconi has been memorialised at Sydney Town Hall with a series of sculptures, still to be found today in the form of a reconstruction of the original equipment, including a radio transmitter, mast and wave connected to a Morse code transmitter and receiver. The location of the memorial is not random, as it recalls a major event that occurred on 3 March 1930, when Marconi transmitted a wireless radio signal directly from his boat moored in Genoa, Italy, in one seventh of a second across the world to trigger all of the Town Hall’s lights ablaze, to the delight and amazement of a spellbound audience gathered on the street.

Now that we have reached the final destination on this walk, those of you who have followed the coordinates will have noticed that these have varied wildly. We have also seen how hard it was to fix time on a given meridian. Let us look back at some of the many determinations made of Sydney’s longitude over the years. Keep in mind that one degree of longitude at Sydney’s latitude is equivalent to a distance of 85km, one minute to 1.42km, and one second is 23.72m. Allowing 0.5km, 1km and 0.5km, respectively, for the changing locations between Ta-Ra, the top of Observatory Hill, and the Fort on Bennelong Point, the varied discrepancies below amount from several metres to a dozen kilometres on the ground.

1788, Dawes determined longitude at his temporary observatory as 151° 19’ 30” E.

1803, Flinders made a calculation at Fort Macquarie of 151° 11’ 49.5” E. = 7’ 19.5”.

1840, Tyers made an estimation at the same location of 151° 15’ 14” E. = 4’ 24.5”.

1859, Scott at Sydney Observatory took a measure of 151° 14’ 58” E. = 16”.

1883, Sydney Observatory by cable time signal from Greenwich: 151° 12’ 22” E. = 3’ 36”.

1904, Sydney Observatory was the basis of national datum at 151° 12’ 23.1” E. = 1’.1”.

2012, the NSW Department of Lands derived a GPS measure for the Observatory’s Trig E of 151° 12’ 4” E. = 19.1”.

2020, Google Earth provided longitude for Sydney Observatory’s meridian at the Transit Telescope of 151° 12’ 13.97” E. = 10”.

It is easy to understand how hard it was to fix a meridian using well-worn instruments and clocks that had travelled around the globe. High precision technologies and the panoptic coordination of orbiting satellites should have solved this problem. It seems not though, given that there was a gap of 10 minutes which equals 237 metres between the GPS measure of 2012 and Google Earth’s position in January 2020.

Does anyone know why this might be? Could it be due to the tectonic motion of Australia, knowing that the continent is moving about 7cm per year? Or is it because of the wobbling poles? And what contribution is climate making to the changes in the shape and gravitational behaviour of the planet?

As it happens, Sydney’s meridian is not the only one on the move! The same phenomenon has been noticed by visitors to Greenwich Prime Meridian, where GPS places the line some 102 metres off it’s original position. One amused tourist traced the location in the nearby park grounds to find that the line ran somewhat ingloriously through a Greenwich council rubbish bin.

Scientists have – made their own speculations on the matter. In 2015, Malys and his colleagues argued, for instance, that because ‘The ground trace of the WGS 84 and the ITRF zero-longitude meridian plane is located approximately 102 m east of the telescope,’ the ‘apparent discrepancy raises questions of how and when it arose, and whether a worldwide system of longitude has been systematically shifted by this same amount’.

While the Earth, on average, still rotates one degree in every 4 minutes, we cannot be certain of any empirical system of measures. If we consider where this endeavour of controlling time began, with the intent of British imperial dominance of the planet via a time-absolute military and spatial network, none of these technologies have helped us to solve the question of how time flows, let alone what conditions the climate crisis on Earth might create. And so it seems that all of our assumptions about an Empire of time are in doubt: everything is in flux.

What time do you really think it is? Myself, I am not sure, but we could always go back to the start to see if the Time Ball can help us calibrate the hour – the clue for our final poster and the end of this walk at Station 24.

Then again, if time is immemorial maybe there’s no need for a beginning at all. But the rift that the Empire of time has wrought on all Australians has not changed the fact that the Earth already possesses its own time and spirit, and that the truth is unchanged as pronounced in the Uluru Statement from the Heart:

Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs. This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago.

This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors. This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and co-exists with the sovereignty of the Crown.

References

Malys, Stephen, John Seago, Nikolaos Palvis, Kenneth Seidelmann and George Kaplan (2015) ‘Why the Greenwich meridian moved’, Journal of Geodesy 89(12): 1263–1272. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00190-015-0844-y

‘Uluru Statement from the Heart’. 2017. Referendum Council. Accessed 12 June 2020. https://www.referendumcouncil.org.au/final-report.html#toc-anchor-ulurustatement-from-the-heart

Postscript

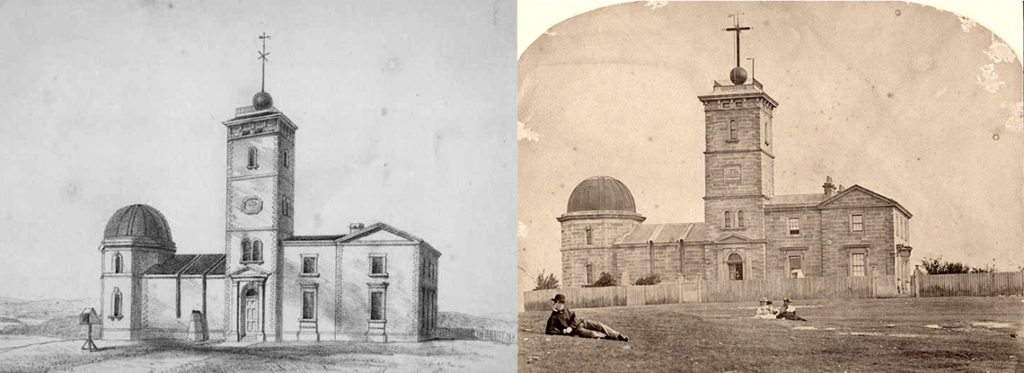

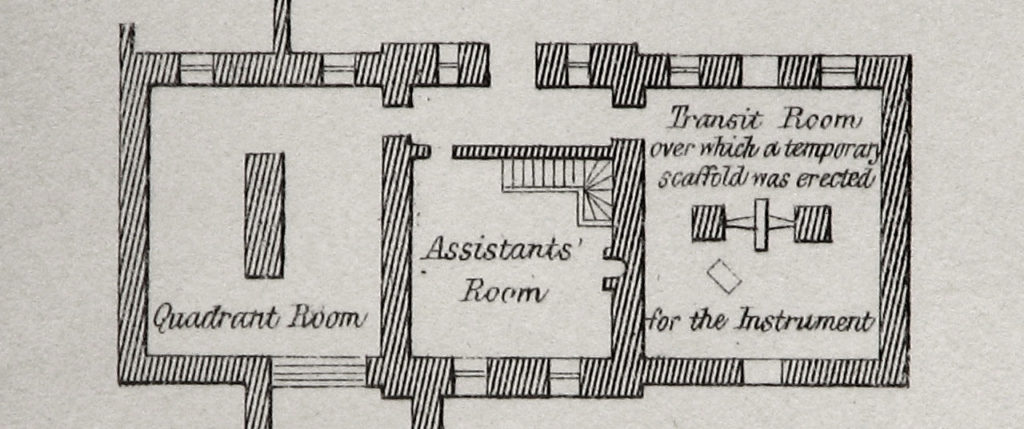

I almost forgot to answer the question of those two shutters on the Transit Room roof back where we began in the introduction to this walk. Immediately after I spoke with Andrew Jacob at the Sydney Observatory last November, I followed up his suggestion that perhaps there were two telescopes in the Transit Room. I could not find any mention of this in the records about the Observatory itself, except that the two openings feature on early illustrations, as in figure 3, which indicates that they were intended from the start, yet I could not determine why.

I did however think of Greenwich. This was firstly because of the moving meridian, but also because I remembered that there had been more than one meridian telescope in the past, and also that the meridian had shifted about eight metres because of this. At Greenwich Observatory today there are still multiple residual shutters but this did not provide any reason for Sydney Observatory having built a roof with two openings from the start.

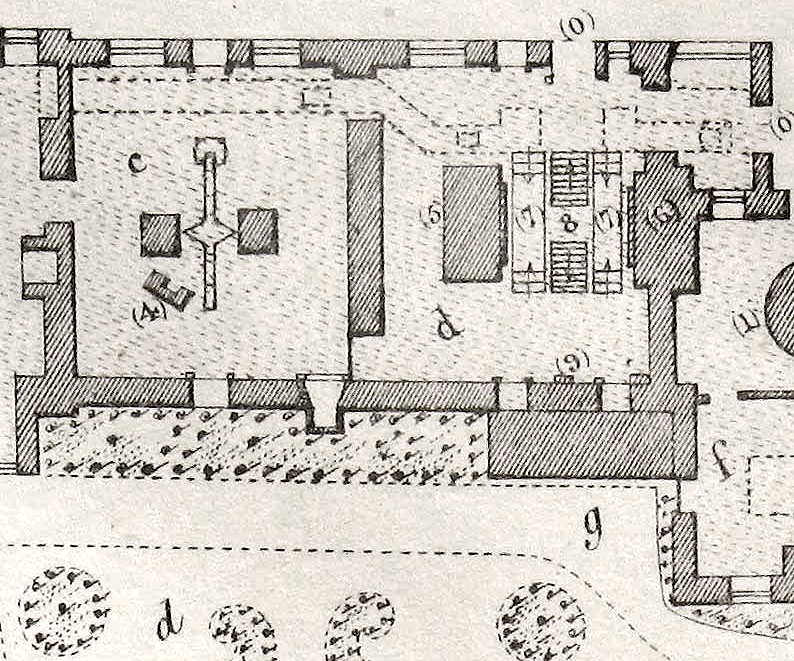

When I began to investigate the question – a task made easy thanks to the exhaustive website created by Graham Dolan (The Royal Observatory Greenwich … where east meets west) – as it turns out, quite a few modifications were made to the buildings to accommodate various transit and circle telescopes at Greenwich over time. Aside from the fact that until the Prime Meridian was decided on, there had been quite a number of different telescopes, I also found that duplicate shutters were present because more than one instrument was being used at the same time – here in figure 4.

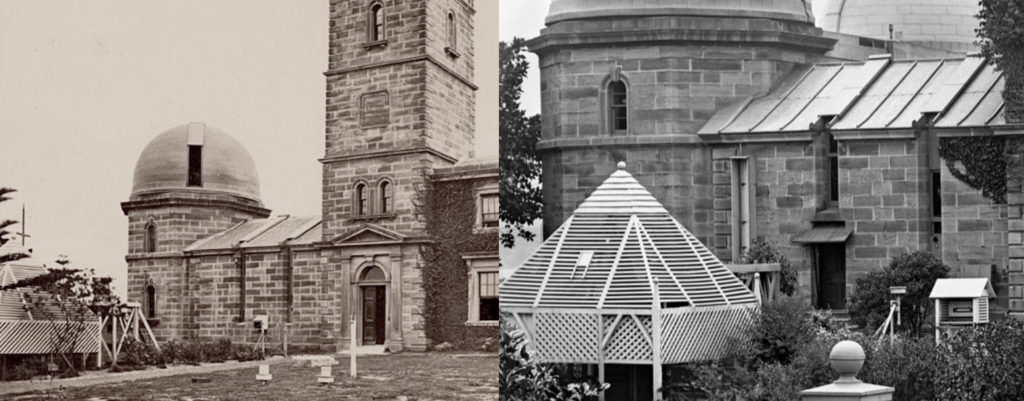

My next mission was to find out if Sydney had indeed had a second instrument, since it was long disappeared from the site. I could not find many photos of the interior of the Transit Room to begin with, so I continued to analyse the exterior – looking for any sign that the left hand aperture was ever used. In figure 6, are two such images: and comparing the one of 1874 with its counterpart only one major difference stands out.

As you can see, somewhere between 1874 and 1917, a door was added (possibly for the convenience of aligning the Transit Telescope with the marker?). But another smaller instrument also caught my attention: the tiny white box in front of the right hand slot, present in both photos but no longer on site today. I noticed a similar object featured also at Greenwich called the personal equation machine. Without being side tracked, the fact that this device remained aligned with only one of the two shutters provides reasonable confidence that there was only ever one meridian defined at Sydney Observatory – even if it had shifted.

What was the reason then for the second shutter? Had the original plan been designed with both a transit and a mural circle room in mind, as was the case at Greenwich? If so, which instruments were used? A mural circle from Parramatta Observatory is noted in Scott’s list of primary equipment (Orchiston, 1998: 25), which had existed to complement the ‘transit telescope’s measurement of star positions’ (Shaping the Domain, 2013).

However Governor Denison had sent it back to London for repairs. As such, until 1859, the only functioning meridian telescope that Scott had at hand was the Troughton transit telescope. Noted in the Powerhouse Museum catalogue, this was the instrument that made ‘the first determinations of longitude of Sydney Observatory an essential step in the surveying of New South Wales. However Scott was not happy with its performance as he felt it had problems with its pivots and axis.’

Whatever the plan, there was no reliable transit instrument installed at Sydney Observatory until 1877 – the Troughton and Simms Transit Telescope still found in situ today. None of this tells us why there were two shutters, except for the fact that two telescopes may have been intended. The only other alternative left is to look for images of the inside of the Transit Room.

Although this final coupling of photographs date respectively from the end of the 19th century to the first part of the 20th century, there are some interesting clues here, for those who seek them. If you enlarge the left hand image, to begin, a second transit pillar appears to be aligned with the farthest shutter. On the right, by 1929, a partition has been erected through the room, however we can clearly see a theodolite sitting on the same pillar, and that it is plainly aligned with the second shutter.

In conclusion, despite my obvious bias for the theory of a shifting meridian, it seems that Andrew Jacob was right from the start – there were indeed two instruments! Enthusiasts and experts are invited to pursue this mystery from here.

References

Orchiston: Wayne. (1998). ‘Mission Impossible: William Scott and the first Sydney Observatory directorship’, Journal of History and Heritage 1(1): 21-43.

Shaping the Domain: The Parramatta Observatory and the Study of the Southern Skies. 2013. Parramatta Park Trust.